I chose to study the effect of surrounding beauty on test performance. I hypothesized that if a student's surroundings include elements of beauty, then they would perform better on an academic test.

Background

To avoid relying on subjectivity, I identified four components of beauty to vary in the two groups of the experiment: life, art, color, and order. In his Critique of Judgment, Immanuel Kant differentiates between dependent beauty, that which is influenced by conceptions of its purpose, and free beauty, that which is not influenced by these conceptions. Scholars such as James Kirwan and Christopher Janaway have applied this concept to the beauty of art and of nature, respectively. Further, according to Kirwan, Thomas Aquinas defined beauty as “a certain proportion and lustre” (Kirwan 1999, p. 57). Throughout history, from Plato to Darwin, both symmetry and light have been strongly associated with beauty (Kirwan, 1999, p. 21, 57, 137; Lorand, 2002, p. 204).

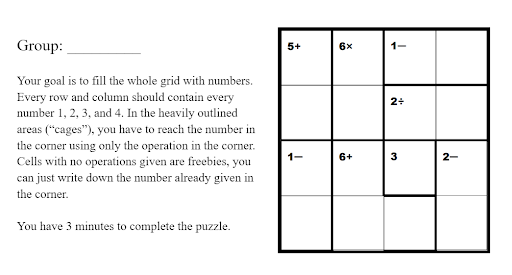

My measure of test performance needed to be largely independent from prior knowledge or classes, as multiple grades would participate in the experiment. At the same time, I could not use an intelligence test, as the ideal intelligence test would not vary based on external factors and so not measure test performance. For these reasons, I chose a relatively obscure but simple logic puzzle, a 4-by-4 KenKen puzzle, to act as the measure of test performance.

Experimental design

The experiment was conducted in a conference room (room 119). This provided an isolated room with little outside noise and no prior mental associations. Subjects would be in one of two groups: the room decorated ugly or the room decorated beautifully. Participants were selected from the first floor cafeteria via a convenience sample.

For the “ugly room”, I largely kept the room as I found it, apart from adding fake dead lotus seed heads to the table in a disorderly fashion [life]. No pieces of art were included, with a blank gray cork board laid on the floor [art]. A large container of antibacterial wipes was left on the table. The room was almost completely beige and gray [color]. The shelves included a range of office supplies haphazardly put away [order]. The data for the ugly room was collected during periods 2, 3, and 4, on Tuesday, May 17.

The “beautiful room” included fake pink flowers on both sides of the table [life, color, order], along with another pink flower in a symmetrical sculpture piece in the center of the table [life, color, art, order]. A painting by a former student was used, as well as a digital art print of London from Michaels [color, art]. The art was positioned symmetrically on the wall [order] and also placed so that it would regularly be in the view of participants. The shelves were reversed to hide the mess previously mentioned [order]. The desk was wiped down to remove dust and particulates that were present in the ugly room [order]. The container of antibacterial wipes was placed on the ground to cover a hole in the floor [order]. Most miscellaneous objects were removed from the room, including the corkboard and a trash can [order]. Data for the beautiful room was collected during periods 4 and 5 on Thursday, May 19.

Participants went through the experiment in pairs. The participants were first asked if they had any prior knowledge of the puzzle in front of them, which was called a KenKen puzzle. One participant from the “ugly room” group and one from the “beautiful room” group had recognized the type of puzzle, but neither had any prior knowledge as to how it was completed. Participants were then given a brief verbal description of the rules of the puzzle, and given an opportunity to ask questions. Once they had confirmed their understanding of the puzzle, participants were informed that they had five minutes to complete the puzzle, and directed to note the analog clock to their right. All instructions given verbally were also listed on the sheet on which they completed the puzzle, apart from the verbal instruction to not work with the other participant and that they were in pairs for “expediency”. All participants received the same puzzle. While participants were completing the puzzle, in both rooms, the door was closed with no view of other rooms or the outside world. I waited in the hallway outside the room for the full five minutes to give the participants privacy and avoid making the participants self-conscious, which would impact their performance.

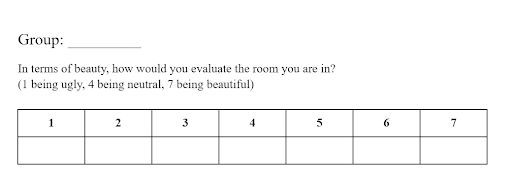

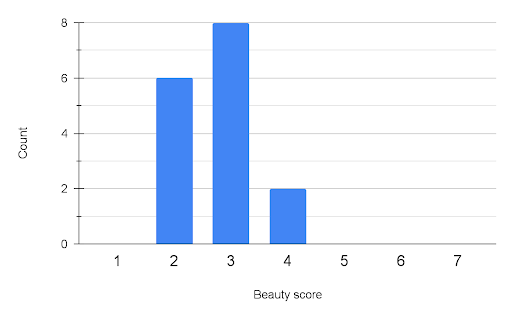

After five minutes were reached on a stopwatch, the puzzles were collected. The participants were verbally asked how well they felt they did, which was not recorded, and then given a second sheet of paper to report the beauty of the room on a seven-point scale. These scores were intended to verify that participants indeed viewed the beautiful room as being more beautiful than the ugly room.

Each participant was assigned a number (1 was the ugly room, 2 was the beautiful room) and a letter (A through P, based on time of participation) to match the beauty score with the test performance. After the beauty score sheets were collected, participants were debriefed on the purpose of the experiment and given an opportunity to ask questions. Participants were instructed to not share information regarding the objective of the experiment; participants were told they could report to peers that they had to “complete a logic puzzle”.

Results

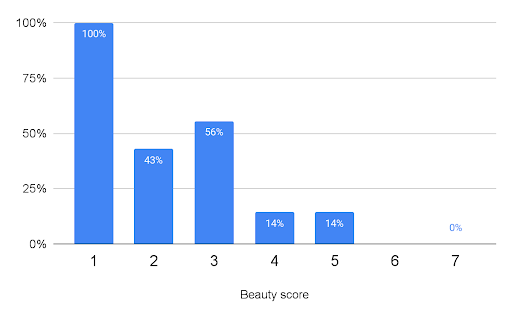

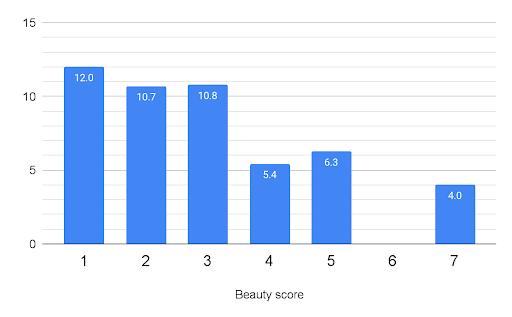

Each group had 16 participants. There were an additional 2 participants at the beginning of the data collection for the ugly room whose results were not counted due to a change in experimental design, specifically the time given to complete the puzzle was extended from three to five minutes. The beautiful room, with an average beauty score of 4.25, was demonstrated to be more beautiful to participants than the ugly room, with an average beauty score of 2.75 (p=0.000541). The beautiful room also sparked more variable beauty scores; though most scores were 4s and 5s, one score of 1 and one score of 7 was given for the beautiful room, while scores for the ugly room were only between 2 and 4.

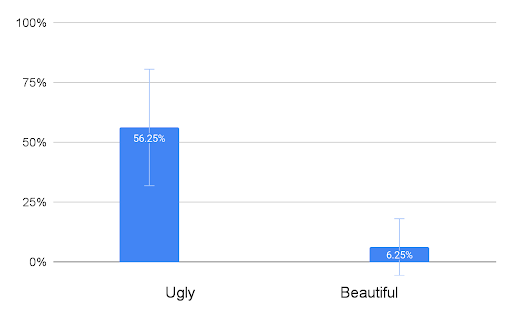

The ugly room had 9 participants (56.25%) correctly complete the puzzle; we are 95% confident that the true proportion of completing the puzzle in the ugly room falls between 31.9% to 80.6%. The beautiful room had only 1 participant (6.25%) correctly complete the puzzle; we are 95% confident that the true proportion of completing the puzzle in the beautiful room falling between 0% to 18.1%. The ugly room was shown to have a significantly higher completion rate than the beautiful room (p=0.00228).

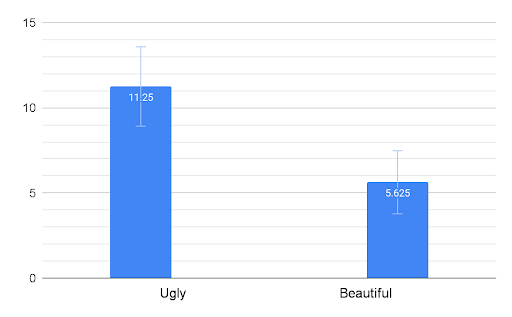

Out of 15 (one cell in the 4-by-4 grid was automatically filled out), the sample mean number of cells correctly filled in the ugly room was 11.3; we are 95% confident that the true mean number of cells in the ugly room falls between 8.9 and 13.6. The sample mean number of cells correctly filled in the beautiful room was 5.6; we are 95% confident that the true mean number of cells in the ugly room falls between 3.8 and 7.5. The ugly room was shown to have significantly higher mean cells correctly filled than the beautiful room (p=0.00243).

Possible confounding variables

It is important to disclose that there were some possible confounding variables:

For one, data was collected on different days and at somewhat different times. This is an issue because (1) schedules, mood, and focus changes throughout the day and week, and (2) due to lunch during period 4 and 5, as well as AP/IB testing, the populations of students available may not have been the same for both groups. There was an IB French test occurring in a nearby room during the latter portion of the collection for the beautiful room, and this may have impacted comfort or focus, and thereby test performance, of the participants.

Additionally, the evaluation of the beauty of the room may have been impacted by the test performance, not the other way around, since the beauty ranking occurred afterwards. However, the hypothesized impact, that high test performance would lead to more generous beauty rankings and a positive correlation, was not reflected by the data, which actually showed a negative correlation. This would not be a confounding variable for the relationship between rooms, which showed a similarly negative correlation. Beauty rankings were placed afterwards because this allows for the test performance to be impacted by a subconscious, not conscious, awareness of the beauty of the room, more closely reflecting what occurs in the real world.

Lastly, the provided pencils were switched to a different kind for the beautiful room due to lack of access to a pencil sharpener, but this shouldn't severely impact scores, if at all.

Conclusion

The initial hypothesis — if a student's surroundings include elements of beauty, then they will perform better on an academic test — was not supported. In fact, the experiment provided convincing evidence that the inclusion of elements of beauty hinders test performance.

There are several possible explanations for this phenomenon. A more pessimistic view is that students are used to ugly rooms and so have been conditioned to perform better in those rooms. Another explanation is that the rooms were flawed in their construction: despite attempts to balance distractions between the two rooms, the beautiful room could have been more distracting to students than the ugly room, hindering performance. My hypothesis is that ugliness is distressing and activates a fight or flight response that benefits test performance, while beauty is calming and reduces stress.

I would be interested in seeing the results of some follow-up studies on this subject. Firstly, perhaps a replication of this study with fewer confounding variables and more participants would give different results. I would also be interested in the effects of surrounding beauty on learning rather than performance. This study somewhat studied the effects on learning since the instructions were given while participants were in the room, but the puzzle had relatively simple rules that were also written on the paper, so memory was not tested. Also, my preferred explanation of the results of this study relies on the potential activation of the fight-or-flight response, so I would like to investigate the effects of known stressors on test performance. Likewise, I am interested in studying the physiological effects of beauty, specifically heart rate, since this could possibly explain if the fight-or-flight response was activated in this experiment.

Work Cited

- Janaway, C. (1993). Beauty in Nature, Beauty in Art. The British Journal of Aesthetics, 33(4), 321–332. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaesthetics/33.4.321

- KenKen Puzzle Rules - How to Play This Amazing Puzzle & Brain Teaser! (2021). Kenkenpuzzle.com. http://www.kenkenpuzzle.com/howto/solve

- Kirwan, J. (1999). Beauty. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Lorand, R. (2002). Aesthetic Order: A Philosophy of Order, Beauty and Art. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.