You might think that an interesting take on identity must focus on identities that are nuanced, layered, and honest. In actuality, understanding how and why many people fall into an oversimplified and stereotypical view of themselves can often tell you more about what identity really is. A key struggle of the human condition is self discovery, as opposed to wallowing in the comfort of simple labels and misunderstandings of oneself. The writers of the TV show Riverdale explore the concept of identity through the nonconformist character of Jughead Jones, who copes with his lack of stability and belonging by viewing himself as an archetype, ultimately showing that such perspectives fail to capture the reality of the world and oneself.

Riverdale is a teen drama and mystery series based on Archie Comics that premiered on The CW network in 2017. The show follows four teenagers: Archie Andrews, Betty Cooper, Veronica Lodge, and Jughead Jones. The town Riverdale is split in two: the poor Southside, where Jughead lives, and the rich Northside, where he goes to school. Jughead is a moody, introverted nonconformist who enjoys mysteries, writing, and reading classic novels. He strives to make good for himself after being left homeless by his alcoholic father, leader of the Southside Serpents, Riverdale's dominant gang.

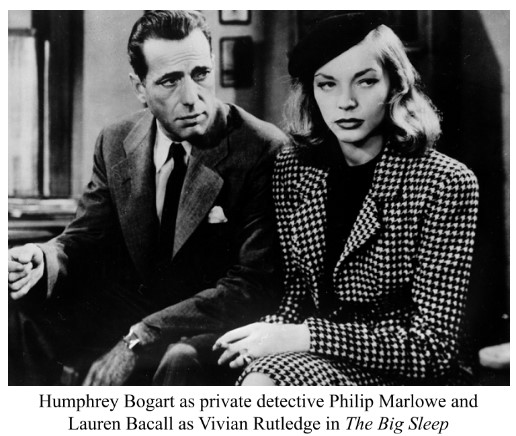

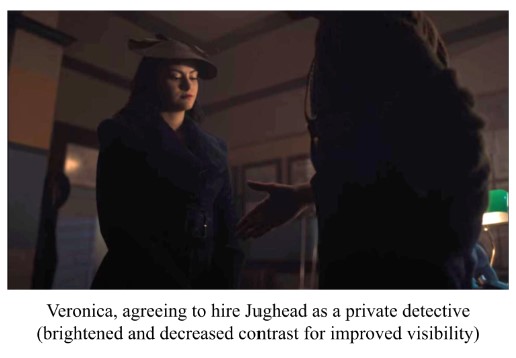

Jughead's vast knowledge of literature and cinema allows him to connect with various characters and archetypes. For example, in season three, Veronica asks to hire Jughead to figure out who shot her father. Jughead accepts the offer, saying, “Well then, consider me your Philip Marlowe,” an allusion to the film noir private detective (“The Red Dahlia” 6:34). In the same scene, Jughead quips, “Nice hat, Bacall,” referring to the actress who stars in the 1946 film The Big Sleep, featuring Philip Marlowe (“The Red Dahlia” 5:39). In fact, despite not being in black and white — that might be a little too on the nose — the entire scene is directed like film noir, from the moody lighting to the jazz music to the subtle downpour. This ambiance makes the audience ponder if the dress and demeanor of a character from a film noir would be consistent with Veronica's disposition and knowledge. The scene could be purely a stylistic choice by the directors, but it seems more likely that the scene, or even the entire series, is told through Jughead's point of view and both the plot and non-plot elements reflect his desired distortions of reality and himself.

Such a perspective actually has more merit than one might think. Firstly, the series features narration from Jughead, who's seen throughout the show writing about the events that unfold on-screen. Secondly, the series features numerous references to old cinema and literature from many characters — references that most modern teenagers, the show's target audience, wouldn't be aware of. But as established before, the character Jughead uniquely has a plethora of literary references in his back pocket. Incorporating these same references in the directorial choices of the show may be how the writers communicate his perspective to the audience. If the series is truly through the mind of Jughead, then the audience can better understand how Jughead views and misunderstands the world and his role in it.

It is clear that Jughead believes that the world is out to get him. For one, the school counselor outright tells him he has a “persecution complex” (“In Treatment” 31:20). This complex is evident in his portrayal of others; given that the events of Riverdale are filtered through Jughead's perspective, almost everything that others say about him in the show portrays how he thinks others view him. An example of Jughead's persecution complex manifesting in the portrayal of others is when Fred Andrews, Archie's father, expresses that he wants to keep his son safe “from whatever trouble seems to follow the Jones's around, wherever they go, whatever they do” (“Anatomy of a Murder” 14:42). When we consider that this line is portrayed through the perspective of, and maybe even in the words of, Jughead himself, it transforms into the epitome of victimhood. In reality, there is no curse that haunts the Jones family; it's easier for Jughead to conceive of an antagonistic force he can fight against than the socioeconomic systems that actually determine his fate but are out of his control.

Unlike his persecution complex, Jughead's outcast complex is evident in his portrayal of himself. A clear example occurs during an argument with Betty Cooper, his girlfriend. After admitting that he would have “actively shunned” his newfound friends only months prior, Jughead delivers lines infused with defective self awareness: “In case you haven't noticed, I'm weird. I'm a weirdo. I don't fit in, and I don't want to fit in. Have you ever seen me without this stupid hat on? That's weird” (“The Lost Weekend” 25:23). Could Jughead's direct admission of his own character traits be, as the antithesis of the literary principle ‘show don't tell’, just lazy writing? Possibly. However, the writers may have written Jughead as a deeper character, one who doesn't admit to Betty how he really is or how he thinks others perceive him, but instead, he admits the role he finds comfort in performing. Jughead later suggests to Betty that they can't be in a relationship because their roles don't align: “Doesn't it ever occur to you just how different we are? Like on a cellular DNA kind of level? You're a straight-A student, you're a cheerleader for God's sakes. You're the perfect girl next door. I'm the damaged loner outsider from the wrong side of the tracks” (“The Lost Weekend” 25:52). Jughead utilizes these opposing archetypes to attempt to explain why their relationship supposedly can't work, but both the premise and conclusion of his argument are far from true. The two are not polar opposites, they share many common interests, like solving mysteries or writing at the Blue and Gold, the school newspaper they co-founded. And they are compatible, evidenced by their healthy, long-lasting relationship. For example, when Jughead later gets the opportunity to go to the prestigious Stonewall Prep for his senior year, Betty trusts Jughead and supports his decision to attend, despite knowing that their final year of high school will be spent schools apart (“Fast Times at Riverdale High”).

So if Jughead's use of these archetypes falls short of the truth, it raises the question why he relies so heavily on them, and as an extension, what the writers are trying to say by making Jughead rely on them. Of course we know that Jughead loves literature, and he may have gathered tropes from his reading, but this doesn't explain why he utilizes these tropes in his perception of reality. It certainly doesn't come from those close to him; when Jughead referred to Betty as the “girl next door,” she interrupted to express her disgust (“The Lost Weekend” 26:05). Jughead utilizes these tropes to attempt to place the unfamiliarity of his situation into concepts he understands and idolizes. For instance, economically, Jughead isn't well off — he is quite literally homeless — but he is surrounded by middle-class and upper-class friends. Additionally, Jughead is shaped by a variety of groups. He is caught in an all out war between the gang-rampant Southside, where he was the son of the dominant gang's leader, and the crime-paranoid Northside, where his friends live. He finds conflict while attending Southside High with poor students, as he doesn't want to engage in the drug trade but instead to focus on his education. He also finds conflict while attending Stonewall Prep with affluent students, as he wants to escape the cycle of poverty that plagued his ancestors, but doesn't want to give into the pompousness of the wealthy preparatory students. His lack of stability and belonging doesn't just provide Jughead stress. It creates complexity and depth to Jughead that can be difficult for him to comprehend and find relief in, unless simplified — even oversimplified — into an easy-to-understand archetype. In contrast to the outcast archetype he places on himself, Jughead does in fact have friends in both the Northside and Southside, and even becomes leader of the Southside Serpents. Thinking of oneself as a loner who doesn't fit in anywhere, as Jughead does, is ironically placing oneself into a group where he can fit in, and this can provide him comfort, despite it not being fully true.

In conclusion, the writers of Riverdale explore identity through the nonconformist Jughead Jones, who views himself as an archetype to cope with his life's stressors and rejections. Life is unfortunately not a novel. We can learn a lot about the world from literature, but to learn about ourselves, we have to move beyond it. We all have the option of defaulting to labels that work for the most part — it is certainly easier and simpler. However, Riverdale attempts to show us that such efforts leave us believing untruths, which inevitably leave us unsatisfied with our real lives and our real selves.

Work Cited

- Grassi, Michael. “Anatomy of a Murder.” Season 1, episode 12, The CW, 4 May 2019.

- Grassi, Michae, and Will Ewing. “Fast Times at Riverdale High.” Riverdale, season 4, episode 2, The CW, 16 Oct. 2019.

- Lundin, Britta, and Brian E. Paterson. “The Lost Weekend.” Riverdale, season 1, episode 10, The CW, 13 Apr. 2019.

- “The Big Sleep.” Harvard Library, 2019, library.harvard.edu/events/big-sleep.

- Turner, Devon, and Will Ewing. “The Red Dahlia.” Riverdale, season 3, episode 11, The CW, 30 Jan. 2019.

- Williams, Tessa Leigh. “In Treatment.” Season 4, episode 8, The CW, 4 Dec. 2019.